By Bill Ward, Newbury resident and historian

In 1897, a family from Gates Mills, Ohio, moved to a 36-acre farm in nearby Geauga County marking the beginning of a multigenerational journey. As the family worked the land, the tilled earth began revealing secrets of its former inhabitants in the form of stone-age artifacts created by Native American people who once called the region home. A family descendent recently explained that all of the artifacts were found over the years while his father and grandfather cultivated crops using a one-hitch cultivator. “It’s a slow process,” he said. “You’re constantly looking down at the ground. That’s how all the arrowheads were found.” A house fire several years ago destroyed all but a few of the once substantial collection. After photographing the remaining pieces, I took the images to Troy resident Mike Fath who is well known for his knowledge of Native American stone work. In the time it took Mike to enjoy a cup of coffee, he had deciphered the secrets of the flint.

All photos: (NEOAC Photos/Bill Ward)

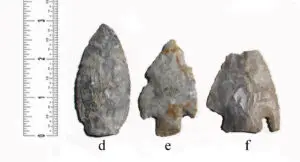

Meadowood Point—2 ,500 BC to 1,000 BC. b. Late Adena Point—100 BC to 200 AD. c. Flint Drill—10,000 BC to 1,600 AD.

Adena Cache Blade—300 BC to 100 AD. Late Adena Points—100 BC to 200 AD. c. Basal Notched Point—5,000 BC.

An Arrowhead in Every Yard

Mike Fath

I asked Mike if it was unreasonable to speculate there being an artifact in every yard, garden or field in the county. He thought a moment and said, “That’s not at all unreasonable. Think of it this way … the land that would eventually become Geauga County was once inhabited by thousands of nomadic people. Imagine if every hunter who passed through the area dropped an arrowhead once a week over the span of 13,000 years. Think of how many millions of artifacts they lost.”

To test the theory of “an arrowhead in every yard,” I contacted several friends who live in the county. Although not a very scientific sampling, nearly all of them or their ancestors have found artifacts on their properties, including me. Below are a few of the more interesting finds.

TROY TOWNSHIP – Hopewell Point – 200 BC to 600 AD. Size: 1½ inches. One of the most common point types in Ohio. (SEGQ Photo/Chuck Fath)

NEWBURY TOWNSHIP – Basal Notched Point – Archaic – estimated date – 5,000 BC. Size – 2½ inches. (SEGQ Photo/Charlene Powell)

MIDDLEFIELD TOWNSHIP – Full Grooved Axe – Archaic to Adena. Mostly granitic stone of glacial origin. Size – 4 inches. Weight – 1¼ lbs. (SEGQ Photo/Ken Stewart)

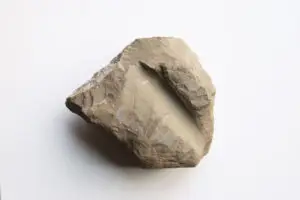

NEWBURY TOWNSHIP – Abrading Stone – 10,000 BC to 500 AD. Used to sharpen or smooth bone, antler or wooden tools. Weight – 5 lbs. Size – 6½ inches at its longest point. Found by this writer.

AUBURN TOWNSHIP – Hammer Stone – Glacial granite. Weight – 2.9lbs. About the size of a softball. (SEGQ Photo/June Fugman)

The Great Migration

Human migration into North America began approximately 16,000 years ago over the Bering land bridge between Siberia and Alaska at the end of the Ice Age. As the ice mass melted, these stone age hunter/gathers followed the food supply into the new world. Moving slowly eastward, these people quickly developed considerable skill creating stone implements. They had long known the use of fire, yet surprisingly, for the vast majority of the time that indigenous people lived in North America, the bow and arrow did not exist. In the eastern woodlands, archery was not introduced until 1,500 to 1,200 years ago. Arrowheads, as we tend to call them, were never attached to arrows in the first place. They were in reality spearheads that could be thrown by hand or hurled with an atlatl, an ancient tool that acts as a lever allowing projectiles to travel farther and faster—sometimes exceeding 93 mph.

Hurling a spear using an atlatl.

After 800 BC, people known as Adena arrived and settled in the Ohio Valley. Some of these people migrated up the shore of Lake Erie close to Punderson Lake.

By 200 BC, the Hopewell people arrived in Ohio. Primarily known for their elaborate burial mounds in Southern Ohio and the Cuyahoga Valley, the Hopewell were peaceful people, like the Adena, who enjoyed living in the safety of fortified villages away from hostile neighbors.

For reasons unknown, following the departure of the Hopewell Indians, the Fort Ancient Indians arrived. They also mysteriously disappeared from the area.

By 1,500 AD, the last wave of migrating Indians known as Woodland, arrived in the Great Lakes Basin and Ohio. The Woodland Indians were categorized into two distinct groups: the Algonquin and the Iroquois. Both Nations, made up of many tribes, were warlike and constantly fighting each other. It wasn’t until after the Revolutionary War that the federal government, land developers and settlers forced the Indians to migrate west. By the time Thomas and Lydia Umberfield settled in Burton in 1798, the Indians were all but gone, except for the signs of their passing.

SOURCE:

Ohio Flint Types. Robert N. Converse. The Archaeological Society of Ohio. 1994.

The History of Punderson Lake. Lou Horvath. Geauga County Historical Society. 1985.